The Medieval Screen at The Bull

A glimpse into a time of religious upheaval?

The Bull is listed as a 17th-century building with a 19th-century façade facing Market Hill. Like many buildings in the square, its Georgian front masks a much older timber-framed structure beneath. Careful examination reveals medieval timbers, large posts, and empty mortices that hint at its Tudor past, including an overhanging jettied first floor and large ground-floor windows, now partly concealed.

A particularly remarkable survivor is an early 16th-century timber screen, still standing in its original position. Built in the plank-and-muntin style with blind Gothic tracery, the screen originally marked the threshold between the public and private areas—a classic “cross passage” layout of late medieval English houses.

This division was not only functional but also symbolic, reinforcing social hierarchy, faith and order.

Architectural historian Timothy Eastwood has written extensively about screens like this, highlighting their dual role as both physical barriers and spiritual protectors. These protective features are common in Suffolk, a county steeped in religious conflict and where fear of malevolent supernatural forces are often manifested in domestic architecture.

Atop the screen is a fragment of embattlement, tinted green, which originally signified the top of the screen before it was infilled in the 17th century. On either side are doors leading to the buttery and pantry—essential service areas for a large household or inn. The carved door head can be seen on both sides. This is chip-carved and a later insertion, most probably of the 17th century.

Scarring on the lower part of the screen suggests that there was once a fitted bench around part of the room which gives hints as to its earlier use as a communal space.

The original purpose of the screen was to provide a separation from the entry passage and the main rooms, but also to add an extravagant architectural touch to the interior. It is a rare survivor of a domestic screen, of a type which we normally see in churches. There was some debate as to whether the screen was repurposed at the time of the English Reformation, but the screen seems to have been specifically built as a grand entrance for The Bull and it’s link to the church may more a subtle act of symbolism.

While the screen served a practical purpose, its features may run deeper. Its construction coincides with a period of religious upheaval. In 1570, Pope Pius V issued a Papal Bull excommunicating Elizabeth I, releasing English Catholics from loyalty to the Queen and effectively encouraging insurrection. The name “The Bull” itself could be a subtle sign of Catholic support and defiance.

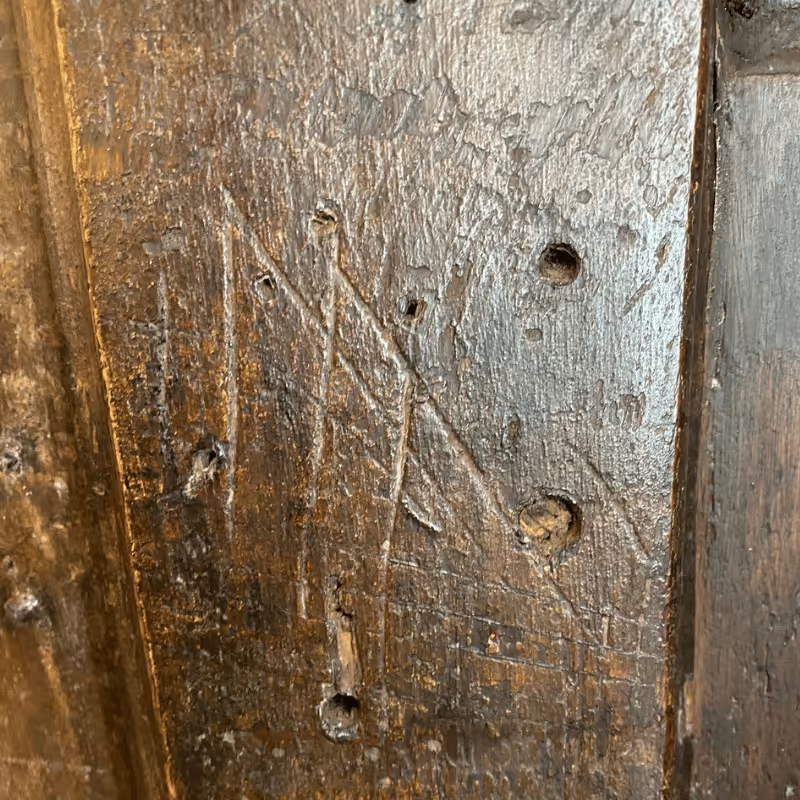

Further evidence of Catholic resilience lies in the screen’s apotropaic marks—symbols like hexafoils, burn marks, the “nine of diamonds” grid, and the ligature of “M” and “A”. During the English Reformation, when open veneration of saints was banned, such marks became coded declarations of faith.

The burn mark is also no accidental feature and is common across East Anglia. The initials “E.B.” scribed with the date “20 September 1675” add yet another layer of intrigue. The fact that the burn mark is central to the initials “EB” suggests that they were done at the same time, perhaps to protect EB or perhaps EB was marking some special occasion, dedication or blessing.

Research reveals that the Rector of St Mary’s Church at that time was Edmund Brome - an outspoken non-conformist known for his independent free spirit. Coincidentally, Pope Clement X, real name Emilio Bonaventura, reigned in 1675. The Rector could have been mischievously signalling his Catholic support. Why display just his initials?

In the Catholic calendar, 1675 was a Jubilee and deemed a Holy Year by Pope Clement, a time when divine mercy was emphasised. Could this be another veiled act of Catholic support in a time of Protestant rule? Whether Brome was simply marking a moment of importance personally or a blessing for The Bull or deliberately hinting at deeper religious tensions is open to interpretation. Given Brome's character, it’s easy to imagine the Rector signalling subtle acts of defiance for his Catholic followers. In an era when Catholics had to be extremely careful, ambiguous public statements would have been the norm. Given this deliberate cloak, the screen at The Bull will no doubt continue to hold its secrets close.

The screen at The Bull is more than just a partition—it’s a testament to the resilience of faith and the quiet defiance of a persecuted community. It stands today as a tangible link to the turbulent religious history of Tudor and Stuart England, reminding us that even in architecture, rebellion can be hidden in plain sight.

Suffolk has always been a strong independent and religious county forged on centuries of conflict. At the time of the Domesday Book, Suffolk had more churches than any other county in England, King Edmund of the East Angles (latterly St Edmund) was killed by Vikings for refusing to abandon his faith and Suffolk suffered more than its fair share of Martyrdoms during the reformation. Many notable families trod a fine line of public displays of Protestant support whilst maintaining, in private, their Catholic faith.

The Bull would like to offer a huge thank you to Timothy Eastwood and Lee Prosser for sharing their invaluable expertise relating to the architectural and historical features of the The Bull.

Nine of Diamonds

The number three has long held protective and spiritual significance across cultures. From Pagan beliefs to Christian doctrine, it is often associated with divine balance, harmony, and power. In Christian tradition, it echoes the Holy Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—a sacred triad believed to offer spiritual protection.

This symbolic power of three also appears in apotropaic practices: rituals, signs, and marks made to ward off evil or malevolent spirits. It’s no coincidence that many protective markings found in historic buildings—especially in medieval and early modern England—incorporate triplet patterns, triple scratches, or circular forms inscribed three times. These patterns were believed to confuse or repel harmful forces.

Shakespeare’s Macbeth reflects this ancient belief system through the infamous three witches, who speak in ritualistic, triplet verse:

“Thrice to thine, and thrice to mine,

And thrice again, to make up nine.

Peace, the charm’s wound up.”

Here, three times three equals nine, a number often regarded as magically complete or fortified. The chant acts as a spell, building power through repetition and rhythm—common techniques in both magic and apotropaic tradition. The number nine, born from three sets of three, suggests a charm fully “wound up” and made effective through symbolic numerology.

Such beliefs weren't just theatrical—they were part of real domestic practice. In places like Suffolk, we find protective marks on timber beams, thresholds, and around hearths, where people once lived in fear of unseen forces. The recurrence of threes in these contexts reinforces the idea that numbers held not just symbolic value, but real protective powers.

This symbolic power of three also appears in apotropaic practices: rituals, signs, and marks made to ward off evil or malevolent spirits. It’s no coincidence that many protective markings found in historic buildings—especially in medieval and early modern England—incorporate triplet patterns, triple scratches, or circular forms inscribed three times. These patterns were believed to confuse or repel harmful forces.

Shakespeare’s Macbeth reflects this ancient belief system through the infamous three witches, who speak in ritualistic, triplet verse:

“Thrice to thine, and thrice to mine,

And thrice again, to make up nine.

Peace, the charm’s wound up.”

Here, three times three equals nine, a number often regarded as magically complete or fortified. The chant acts as a spell, building power through repetition and rhythm—common techniques in both magic and apotropaic tradition. The number nine, born from three sets of three, suggests a charm fully “wound up” and made effective through symbolic numerology.

Such beliefs weren't just theatrical—they were part of real domestic practice. In places like Suffolk, we find protective marks on timber beams, thresholds, and around hearths, where people once lived in fear of unseen forces. The recurrence of threes in these contexts reinforces the idea that numbers held not just symbolic value, but real protective powers.

Integrated MA

The interwoven M and A symbol—representing Maria, the Virgin Mary—was commonly inscribed as a protective device. Believed to ward off evil, it appealed to the Virgin’s role as a spiritual guardian. The interlaced design of the initials may have served a dual purpose: offering discreet devotion while concealing its true meaning. During the English Reformation of the mid-16th century, open veneration of saints and religious icons was forbidden, so such marks likely became a subtle act of faith, hidden in plain sight.

The Deliberate Burn Mark

This is no accidental feature – these burn marks can take some time to build up and are very typical across East Anglia. The act of placing a deliberate burn mark on the screen seems to serve as protection from further harm. The marks also seem to be placed at entrances and fireplaces to ward off evil spirits entering the property.

The fact that the burn mark is central to the initials “EB” suggests that they were done at the same time, perhaps to protect EB or perhaps EB was marking some special occasion.

The fact that the burn mark is central to the initials “EB” suggests that they were done at the same time, perhaps to protect EB or perhaps EB was marking some special occasion.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)